The future is a dark, desolate place. Only those who control the spice control the universe.

What’s the concern

It’s known to all that the large pre-trained models consume tremendous energy for the sake of parameter fitting and model inferencing. For instance, the researchers from HuggingFace and Carnegie Mellon University tested 88 different AI models across various tasks, finding that most tasks consumed minimal energy, equivalent to watching nine seconds or 3.5 minutes of Netflix per 1,000 repetitions (see here for more details). However, image-generation models proved notably energy-intensive, using almost as much energy as charging a smartphone to produce a single image.

In this blog post, I will explain how artificial intelligence models consume energy from multiple levels, ranging from the compilation and execution of computer system programs to underlying hardware and chips.

How AI model works

While it may not be scientifically accurate to label the large language model (LLM) as equivalent to an AI model, hereafter the term “AI” model specifically refers to the foundational model utilizing deep learning algorithms for predictive analysis. It is important to note that the subsequent sub-section detailing low-level computing system specifics applies to all types of AI models, where the computations are typically executed on silicon-based hardware. We will analyze how artificial intelligence models consume energy at the computer hardware level through two distinct processes: model training and model inferencing.

Training

The contemporary AI models were developed by using the programming languages like Python, C/C++, etc. At the high-level point of view, building an AI model requires programming the layer representations of deep neural network and fitting the parameters of each layer to maximize the likelihood of predicting the values as pre-defined. GPT-4, the latest language model from OpenAI, consists of 1.76 trillion parameters. Without loss of generality, the computations involved in pre-training an AI model are usually found in the steps of

- Feed-forward calculation of the output of layers of the neural network.

- Back-propagation of the gradient with respect to the objective function.

The above steps are parallelized such that computing gradients with multiple combinations of parameters can be accelerated. There are additional components than just the fully-connected layers in the neural network of a complicated model. For example, the commonly used neural network modules such as drop-out, multi-head self attention, residue network connection, etc. are found in the typical AI model like BERT. Computation-wise, these components might either add more model parameters in total (e.g., number of total self-attention heads, number of hidden layers, etc.) or introduce complexity in the model structure (e.g., the quadratic increase of complexity due to pairwise token interactions in the self-attention).

For example, in Python, a deep learning model can be built by using torch by

“stacking” the nn.Module as the basic blocks in the codes. The following shows

an illustrative version of the “transformer” model built with torch. Without

loss of generality the detailed implementations of the layers are not shown in

the illustrating codes.

"""

This is the definition of a simplified version of the transformer model.

"""

class TransformerModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_size, output_size):

super(TransformerModel, self).__init__()

print("Define the layers of the transformer model.")

def forward(self, x):

print("Define the forward pass of the model.")

return x

The training process is the iterations of parameter-fitting by using the initial state of the pre-defined neural network topology on the training samples. And usually, training is conducted on GPU devices at scale to parallelize the fitting steps, called “epochs” with the training data. With the above “transformer” example, the training process can be implemented as the code snippet below.

"""

This is the definition of the loss function and the optimizer function for

training the transformer model.

"""

criterion = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

optimizer = optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=learning_rate)

"""

The training loop iteratively find the parameter values which optimally yield

the minimized loss with regard to the objective.

"""

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

for batch in train_dataloader:

# Get input and target from the batch

inputs, targets = batch

# Zero the gradients

optimizer.zero_grad()

# Forward pass

outputs = model(inputs)

# Calculate the loss

loss = criterion(outputs, targets)

# Backward pass

loss.backward()

# Update the weights

optimizer.step()

# Print or log the training loss for this epoch

It is intuitively obvious that the energy consumption of the above model building process is mainly determined by the energy consumption for each epoch and the total counts of epochs used by training the model. The unavoidable computational cost incurred by the multiple iterations required during the training of deep learning models is closely related to the execution time of each iteration during the iterative process, as well as the computational tasks required for each iteration. As will be discussed in the following parts, the exact amount of the energy is determined by the underlying hardware being used in the computer system.

Inferencing

Compared to the model training process, inferencing is unidirectional in computing the output of each layer in the neural network representation of the model, because only feed-forward is needed. The energy consumption is highly attributed to the model topology, which in turn, is determined by the use case of the AI model. Compared to model training, model inferencing consumes less energy, because there is no repetitive steps for objective optimization. Still parallel computing can be applied because sometimes the inferencing part requires low latency.

The same methodology can be applied to the energy consumption estimation for the model inferencing part, i.e., the total energy consumption is the multiplication of the power consumption of hardware and the time for performing an inference task.

Hardware

As we delve deeper into the computer’s architecture, we encounter the point where the program, responsible for either training an AI model or conducting inference with a pre-trained one, is executed. The energy consumption originates physically from the computer hardware. The extensive utilization of CPU, GPU, memory, and potentially disk devices collectively leads to significant electricity consumption when constructing a large AI model with billions or trillions of parameters!

Computer system

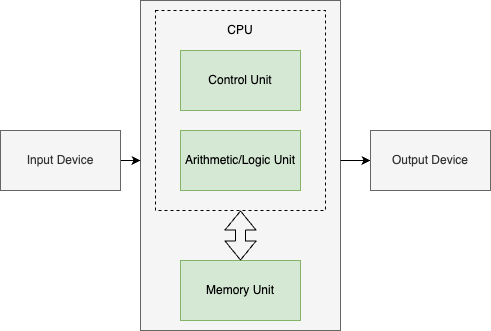

The contemporary computer system follows the Von-Neumann structure (probably let’s not argue about whether this is the optimal choice for artificial intelligence). The Von-Neumann architecture normally consists of a central processing unit (CPU), memory, and the I/O devices with the bus connection with other components. Notably GPU is an exception to the general-purpose CPU device in the Von-Neumann architecture due to is specialty in dealing with computer image related computations - general purpose GPU or “AI-application-specific” GPU does not essentially change the nature of GPU architecture though optimization has been introduced to favour large-scale numeric computation like mat-mul or so.

Each of the computer system components consumes energy in processing programs regardless of whether it is for AI model or not.

- In a CPU, instruction fetch, instruction decode, processing instructions in execution units, read from and/or write to cache, etc., all consume energy.

- In the memory or cache, data read/write operations incur power and energy consumption. The same applies to the data I/O with disk drives (either hard-drive disk or solid-state disk) or other storage medium.

The codes written by using the high-level programming language for building the model are “translated” into the machine codes for the actual execution on the hardware. This process, in general, is called “compiling”; the aim of compiling is to represent the same information in the high-level codes into a low-level machine binary executables. For example, assuming an AI model is being trained iteratively in a program. When the for-loops are being executed to find the optimal parameter values for minimizing the loss, these commands are compiled into the “instructions” which are then sent to the CPU device for processing. The following shows example (see reference here) assembly codes of a x86 machine, where a function is called to proceed with the three input parameter values.

push [var] ; Push last parameter first

push 216 ; Push the second parameter

push eax ; Push first parameter last

call _myFunc ; Call the function (assume C naming)

add esp, 12

When processing the program, the above assembly is further compiled into the binary code (for the sake of simplicity, the compiling process is not detailed). The following shows the disassembly machine codes (binary code presented as hex) that are converted from the above example.

0: ff 35 00 00 00 00 push DWORD PTR ds:0x0

6: 68 d8 00 00 00 push 0xd8

b: 50 push eax

c: e8 fc ff ff ff call d <_main+0xd>

11: 83 c4 0c add esp,0xc

Before any actual computation happening in the CPU/GPU, the data required for the computation are firstly loaded from the memory and then sent to the CPU or GPU for computation. The CPU/GPU clock frequency usually determines “flops” of the instructions in the machine where the actual logic is processed - this will determine how fast the program can be executed in the computer. After it, the result data is written back to the memory. If needed, the result is saved to the disk. As aforementioned, each of the step consumes energy at various places when the activities of relevant system components are conducted.

Low-level physical device

Indeed, even a close examination of the computer system fails to provide us with an answer regarding the source of energy consumption as taught by physics. When the Python program for constructing an AI model is translated into low-level machine codes for processing on CPU/GPU and memory, how does this process consume electrical power? To find the answer, further exploration of the underlying structure of a computer is necessary.

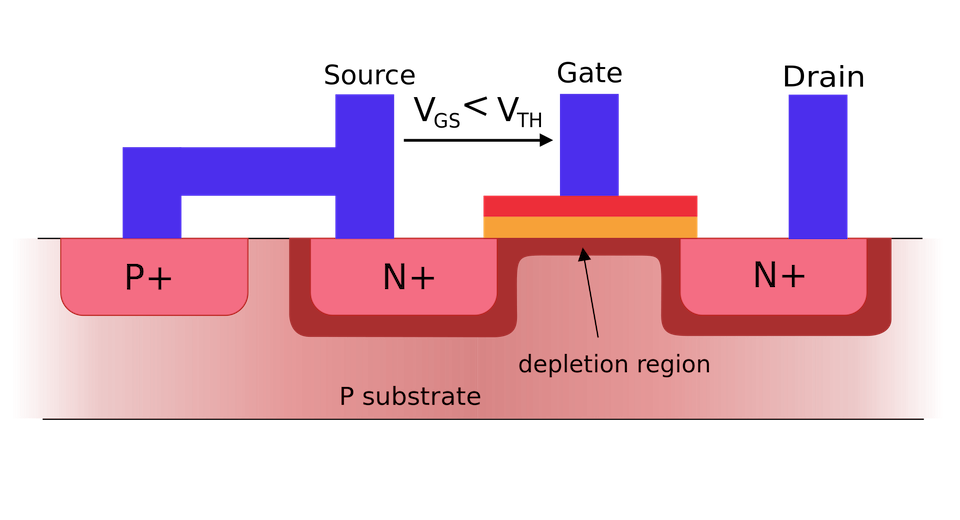

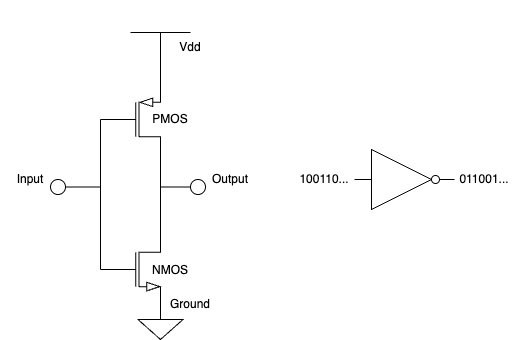

As we may know that the CPU and memory devices in the modern computer are made of transistors. The transistor is a semiconductor device that is used for switching its state given different input power as signals in the digital system. Transistors are the fundamental yet essential elements in a computer system hardware. Considering the most common implementation technology of Metal-Oxide Field-Effect Transistor (MOSFET), it is a four-terminal physical device where the four different terminals, defined as drain, gate, source, and body (see the figure as attached for illustration), are connected in an integrated circuit or system to function as either digital gate or logic amplifier. The equivalent circuit of the transistor is a complex of resistors where current is through when it is applied with voltage. As a fundamental Physics theory, the power dissipated by a resistor is

\[P=I\times V\]which is equivalent to $I^2\times R$ or $\frac{V^2}/R$, where $I$, $V$, and $R$ refer to current, voltage, and resistance of the resistor, respectively.

Given the complexity of the equivalent resistance of a MOSFET, in general, the power dissipation of a MOSFET is mainly due to its drain-source equivalent resistance. Imagine the transistor states are in either “1” or “0”, depending on whether the current is through the drain-source route with the gate terminal being “on” or “off”, the total power dissipation will be $I\times V$ where the $I$ and $V$ are the current and voltage applied to the transistor in the particular state. The on and off of the transistor is controlled completely by the input signal passed on to the gate terminal. That is, if the input is “1”, it is on; if it is “0”, it is off. The “1-0” signal sequence is determined by the program, which is exactly the machine codes that run in the CPU or GPU.

Modern CPU or GPU devices have millions or billions of transistors. When a program is sent to CPU or GPU devices, the machine codes that eventually execute the program switch on and off the transistors… This is where the power is dissipated, and in turn, during some period of time, the electrical energy is consumed as $P\times t$.

Thinking about the above process again, the ultimate source of energy consumption of an AI program that runs on a digital hardware is the transistor devices. And the volume of energy consumption depends on how many flops of the “0-to-1” or “1-to-0” process inside the hardware devices. NOTE, though the above discussion is mainly about the computation unit of the system, the modern memory chips and even solid-state disk, are fabricated with the semiconductor technologies. And the energy in utilizing these device is dissipated in a similar to CPU or GPU devices.

Putting things together…

Now, let’s transition from the realm of physics back to computer science and contemplate the entire energy consumption process for an AI model.

- For the model training part, the training process which is written as computer program, runs on a computer system.

- To find the model with the optimal performance, the training is executed in parallel to search for the best parameter combination.

- Each of the training process, called “epoch”, is translated into low-level machine code by the compiler of the system.

- The low-level machine code is executed inside the CPU/GPU devices as 0-1 sequence.

- The 0-to-1 or 1-to-0 switch of the logic states conduct the underlying MOSFET devices in the computer hardware, which then dissipate power of electricity.

It is nearly the same process for the model inferencing part so it’s not repeated here.

Closing

Factors of energy consumption in software and hardware

Knowing the underlying details, there are several key factors of the energy consumption of a model from both software and hardware’s perspectives.

From the software’s point of view, the energy consumption of an AI model is mainly determined by the following factors

- The complexity of the AI model, i.e., # parameters, topology of neural network, etc.

- Configuration of the training process, i.e., # epochs, # parallel threads, etc.

- Configuration of the inference process, i.e., # endpoints, # model replicas, etc.

From the hardware’s point of view, the energy consumption is mainly affected by

- The hardware configuration, i.e., clock frequency (this determines the # flops of the 0-1 state within certain period of time), electrical config of the system (voltage), system voltage, etc. For example, the most latest nvidia AI chip, “Blackwell”, achieves 20 petaflops in AI performance versus 4 petaflops for the last generation, H100. And this throughput may incur higher power consumption compared to the old-generation, too.

- The device technology. i.e., the size of the transistor, # transistors, etc.

How do we mitigate the issue?

It is obviously that energy efficiency of AI requires a collective effort from both the model developer, software engineer, and hardware engineer.

At the level of model algorithm and software program development, the engineers and scientists are required to properly choose the algorithm and implementation of an AI model to tackle the problem - for deep neural network-based algorithms it is advisable to apply pruning to make the model light-weight. One of the possible directions of developing the foundation model is to make it “small”. The benefits of the small models are that, they have much smaller space of parameters but comparable performance against some large models (see MobileBERT, DistilBERT, Phi2, BERTmini, etc.). Another category of efforts is put onto the training techniques where the optimization process for building a deep-learning model can be enhanced with computational efficiency. Tricks in such group include neural architecture search, neural network pruning, etc. At the inference stage, people have done research to enhance energy efficiency, too. It was found in the research by the HuggingFace team that, even for the same task, different model architectures may lead to different levels of energy consumption. And thus, at the design phase, choosing the appropriate architecture of model is a key design constraint.

At the low-level hardware design and development, researchers and practitioners are making efforts to introduce new device, circuit, or system technologies for low-power or low-energy implementation. Most of the modern computer system has the dynamic voltage scaling mechanism to control the voltage of CPU/GPU chip for the best use of electricity. Clock gating and power gating are the commonly used techniques in keeping transistors in circuits off at the time when they are not needed, such that the power consumption of these “off” circuits is minimized. Researchers are also investigating in novel semiconductor materials for fabricating AI chips with ultra-low-power capability. For example, IBM developed the newest prototype chips use drastically less power to solve AI tasks, which yields 14 times more energy efficiency compared against the baseline.

It’s not trivial to lower the energy consumption of AI workloads in general due to the factors at different hierarchies inside a computer system. Nevertheless, it is never too late to have a good sense of the criticality of the issue and take actions. It must be said that, many times, the focus on the energy efficiency of artificial intelligence models has been overshadowed by their ‘bright spots’ in other aspects, which means that even when many scholars and experts are aware that energy efficiency could be a serious social and environmental issue, they still prioritize the commercialization and proceduralization of artificial intelligence models. The problems brought about by this approach may gradually become more apparent in the near future, and the failure to timely address the technological and ethical balance may further exacerbate the consequences of these problems.

References

- Alexandra Sasha Luccioni, Yacine Jernite, and Emma Strubell, Power Hungry Processing: Watts Driving the Cost of AI Deployment?

- Jesse Dodge, Taylor Prewitt, Remi Tachet des Combes, Erika Odmark, Roy Schwartz, Emma Strubell, Alexandra Sasha Luccioni, Noah A Smith, Nicole DeCario, and Will Buchanan. 2022. Measuring the carbon intensity of AI in cloud instances. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. 1877–1894.

- Alexandra Sasha Luccioni and Alex Hernandez-Garcia. 2023. Counting carbon: A survey of factors influencing the emissions of machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.08476 (2023).

- Alexandre Lacoste, Alexandra Luccioni, Victor Schmidt, and Thomas Dandres. Quantifying the carbon emissions of machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.09700 (2019).

- Lasse F. Wolff Anthony, Benjamin Kanding, and Raghavendra Selvan. 2020. Carbontracker: Tracking and Predicting the Carbon Footprint of Training Deep Learning Models. arXiv:2007.03051

- MLA. Rabaey, Jan. Digital Integrated Circuits : a Design Perspective. Englewood Cliffs, N.J. :Prentice Hall, 1996.

- Kimberley Mok, The Rise Of Small Language Model, The News Stack, 2024.

Citation

Plain citation as

Zhang, Le. Where does the energy go - Understanding energy consumption of AI models. Thinkloud. https://yueguoguo.github.io/2024/03/10/where-does-energy-go/, 2024.

or Bibliography-like citation

@article{yueguoguo2024energy,

title = "Where does the energy go - Understanding energy consumption of AI models",

author = "Zhang, Le",

journal = "yueguoguo.github.io",

year = "2024",

month = "Mar",

url = "https://yueguoguo.github.io/2024/03/10/where-does-energy-go/"

}